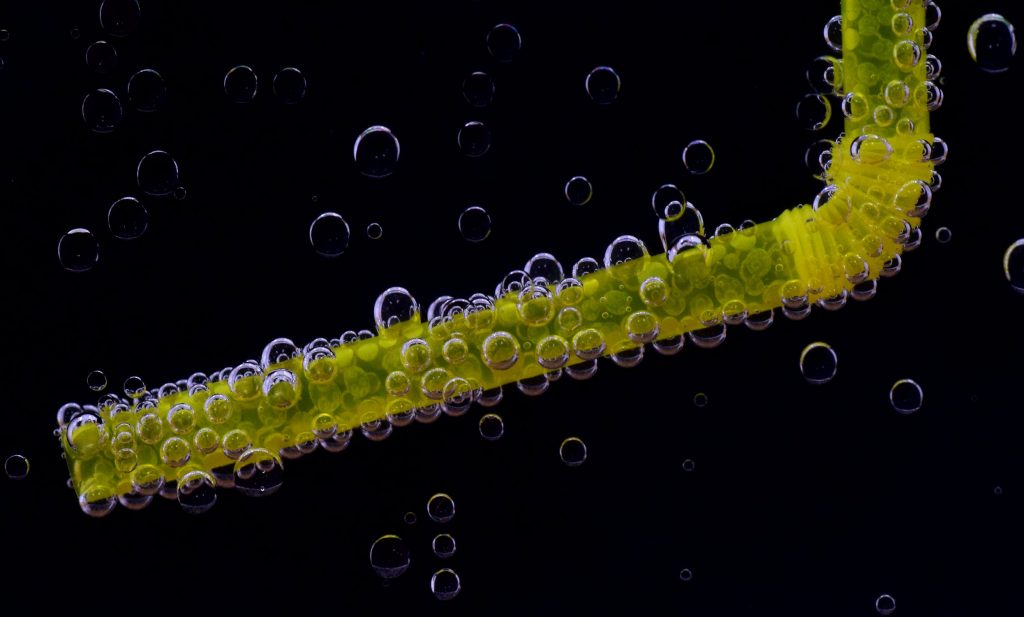

To a varying degree, McDonald”s around the entire planet are currently talking about going straw-free.

In Ireland and the United Kingdom, the fast food giant will be phasing straws out entirely across all its 1,361 restaurants, and, around the rest of the world, there’s talk of a more earth-friendly paper-straw implementation plan. (If you need more background on why something as seemingly harmless as a straw is such a threat to the planet and its wildlife, this is a great place to start.)

The change happened, in large part, because consumers applied the pressure, as evidenced by this petition drafted by the group SumOfUs. As a result, McDonald’s said it will start testing alternatives to plastic straws at select locations in the U.S. later this year—this comes after the news from less than a month ago that the majority of its board voted against the measure to change the plastic straw policy in the U.S.

This got us thinking about the motivation behind what leads a company to make a decision like that—and what exactly their timeline is. A choice to decline a straw might seem small if someone like you or I did it, but could seriously impact the world if someone, or several “someones” at a major corporation decided to say “Yep, it’s a go.”

We also couldn’t help but notice just how quickly Starbucks began shutting down and implementing sensitivity training after the racially charged incident earlier this year. It’s probably fair to say that we have all seen examples that huge enterprises act with lightning speed when the pressure is on.

To be sure, large companies do have decision processes and due protocol in place for a reason. These “chains of command” and other established systems serve a purpose but do make change more gradual. What is that moves these big machines forward, sometimes at such speed?

Nicholas Luff, an advisor and strategist with over 25 years experience in the corporate, nonprofit and public sectors, believes that the bigger picture “hold up” it’s partially due to fear around whether the planned change is going to align with the expectations of their key stakeholders—management, major shareholders, customers.

“In today’s world of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), most companies are looking for a cause that seems to be in the sweet spot between their core business values and their willingness to invest in the communities in which they work,” he said.

“One of the industries that has made impressive CSR changes, including protocols, is mining and metals. A U.S. based company might know that they must engage with a local community from which they extract minerals as they need a ‘social’ license to operate…that is, enough acceptance from the community so as to reduce the chance of protest, negative media exposure, perceived negative consequences that are associated with the its presence.

It’s easy to see the connection there between social contribution and stakeholder expectation. These actions literally help them move their operations forward. We can see this connection between impact and business operations in other examples. Google achieved its 100 percent renewable energy target in 2017, and is now the largest corporate renewable energy purchaser on the planet, ….so did Levi Strauss, whose reduction and specific use of water in the creation of their jeans has saved more than 1 billion liters of water since 2011, according to their website

Then, of course, there are the folks who build socially responsible practices into the very business model, like Tom’s Shoes give-one-get-one model, and Ben & Jerry’s early refusal a zillion years ago to refrain from using a growth hormone in cows that was incredibly popular and widely accepted in the late 80’s.

Companies like these took an opportunity to be seen as leaders of social good when they made a decision and implemented a positive change quickly. A mere decision to “look into an issue” or theoretically “make a change” with a really long timeline, takes away all of the positive brand power of that action.

Consumers hear that a company is “looking into it” and we are not inspired. When we hear what seems like a really long timeline we’re going to just group it in with all the other next-to-never announcements we hear by government and big business. Part of this is managing the message—if you’re literally “just looking into it” without intention to move on it anytime soon, just don’t bother with the announcement. The market is much less interested in what you “might” do than what you “will” do, and talking about maybes might actually damage your credibility as a company that takes action.

When it comes to business, a giant decision that affects millions may take longer than we’d all like because of that aforementioned processes. But think about this: can a decision be implemented in stages to accelerate action with baby-steps? Can your exploration of an issue be accompanied with some positive steps to demonstrate action? Afterall, some progress is better than waiting for perfection. Or better yet, can the organization find the strength to find it’s issue of focus and act like their reputation depends on it? How fast could this be done, if it had to be?

And how can we consumers make it clear to companies, that we do believe social change really is urgent? Maybe for now, just like the folks who caused movement in the McDonald’s straw decision, that’s on us.